Scarcity creates tension and meaningful choices in board games by deliberately limiting resources, whether through finite action spaces, limited card draws, or countdown timers. This constraint transforms simple decisions into strategic puzzles, forcing players to prioritize and consider opportunity costs. When implemented effectively, scarcity doesn’t feel punitive—it creates the satisfying challenge of optimization that keeps players engaged and invested in their choices.

Board games mirror economic principles through scarcity-based mechanics, creating systems where players experience supply and demand firsthand. Limited resources force trade-offs and opportunity costs that echo real-world decision-making. Oftentimes, the use of scarcity makes a game an economic one more than one might expect.

When playing games and considering their designs, it’s fascinating that so many of the best games are painfully tight; where every last single resource is precious and hard-earned. If we think about the opposite of scarcity, we can understand why this matters. If we get more than we will ever need of a resource, why have the resource at all? This sounds super boring. Imagine a game where you have unlimited money. Wouldn’t that make money irrelevant? I actually say that ironically because the first example I want to talk about actually gives players unlimited money.

QE

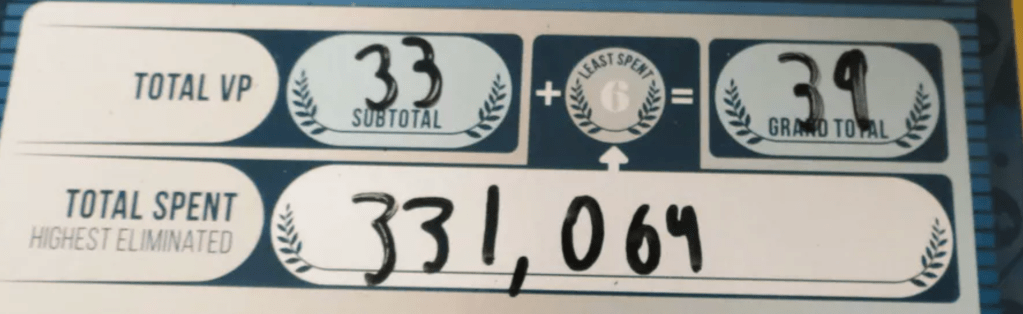

In the game QE, players are secretly bidding to buy companies. The trick is that money is unlimited; you can literally bid any amount of money you want. While this article is about scarcity, I think it’s interesting to consider how to break this aspect of game design. There is obviously a twist to the game that makes it interesting: the player that bids the most over the course of the game loses all of their victory points. So, you want to buy all you can while not being the person to spend the most money. Without that aspect, there would be no point to the game. It just goes to show that a great way to come up with game design ideas is to look at concepts and think about how you can break them. Next, let’s look at some samples that do have scarcity and how this impacts gameplay.

Imperial Steam

In Imperial Steam, you start off with a good amount of money, but it’s deceptive. Money is very hard to come by. If you do not plan for a way to get additional funds, you can find yourself in a very real bind. Money and resources are extremely limited, and opportunities to acquire them are used once and can’t be used again. This forces players to push farther into the map. I am sure it is very hard to balance an economy to be this tight and still create lots of paths to explore. But Imperial Steam rides that narrow path well. Its use of scarcity is extremely tight and punishes those that fail to plan ahead.

Power Grid

Power Grid is a game that frequently comes up when talking about scarcity and economics in board games. In the game, there is a marketplace of resources. When the market is flooded with a resource, the price goes down. But as inventory drops, the price goes up. Each round, a set amount of product is added back to the market. It is a really simple system, but it enables the players to create scarcity in the game. If too many people go for coal-powered plants, the price of coal is going to shoot up. Be the first to get a nuclear plant, and you will find uranium is cheap…until someone else enters that market. This system forces player interaction in a very unique way. Scarcity is a key ingredient of the game that drives players to push for better power plants.

While Imperial Steam does have some player-driven elements, it is mostly that the challenges of the game make resources scarce. Players race to gobble up the resources before they disappear. In contrast, Power Grid relies on the players to establish the value of different commodities. Neither is better, of course; it’s just very interesting to consider how to approach this.

Settlers of Catan

Settlers of Catan is another popular game to talk about when it comes to scarcity. One obvious way the game does this is through resource production. If players are overproducing a single good, then that good will have less trading power. If, in contrast, a good is hard to come by, it will rise in value and competition for it will be more fierce. On the surface, this is clearly using player-driven scarcity. However, there is another layer to this that makes the game really ingenious. The robber moves around the board, blocking resource spaces. Most players see this as preventing a single player from collecting that given resource, which is true. But this also means that the targeted resource is going to be that much harder to come by. This tends to escalate the scarcity situation and can drive the value of a single good up in a significant way. As a player, it’s good to consider who you are blocking, but also what you are blocking. Is it a resource you don’t need yet? Or maybe it’s one only you will be able to produce as a result of the block? Thinking beyond the obvious aggression towards the winner reveals an interesting layer of scarcity used in the game.