An important usability aspect of digital systems is that they should not rely too heavily on users to remember things. This is especially true as the world has evolved into one where the ability to find answers is more important than the ability to memorize them… but that’s a totally different subject. In regards to board games and player experience, it’s also very important to limit the degree to which you rely on players’ memories. This is something the industry has naturally accounted for. Over the last 20 years, we have seen a growing design trend where player aids, round guides, and other tools have been used to reduce memory load.

There is some nuance to this, though, because in some games the memory aspect is actually important or even thematic and might even be a skill factor. Take poker, for example. Counting cards will get you kicked out of a casino, though it doesn’t break any rules of the game. They just don’t want you to increase your odds of winning. That said, it’s a skill, and if you are able to do it, you will find that your odds improve. And of course, there are games like the classic Memory, where using your memory is literally the point of the game.

One example I want to start with is Honey Buzz. In one aspect of the game, you have bees flying around collecting nectar for your hive. The rules offer two options. In the first, you simply put the nectar tiles out face up for all to see. The second is to put them face down randomly. The second option better emulates the theme of bees flying about looking for the right nectar. This means players must not only remember what they have seen on the board (assuming they didn’t pick it up), but they must also track how many of each have been found. This is definitely an extra memory load for the player. For many, this memory aspect and hunting around feel too random. So the rule is wisely presented as an option for players to choose. I am not normally a fan of alternate rules, as it just feels like designers lack a vision and purpose. However, in this case, I think it’s a wise choice that strongly affects how players feel about things.

In some games, the memory aspect is minimal and therefore not really a problem. Champions of Midgard has a very reasonable element that players must memorize. When taking a specific action in the game, you get the chance to preview one of the event cards, which must be resolved before fighting one of the big monsters. These little event cards can hinder you, present another minor enemy to fight, or be nothing at all. So knowing what it is ahead of time helps you prepare for it, or avoid it. There are only a few of these cards, and you can only see up to a single one per round. The memory load is reasonable, and the game doesn’t require any kind of aid.

A favorite game in my house is XenoShyft. This tower defense deck builder is cooperative and has a lot of really neat things happening. But one negative is that many cards modify others. They do things like give health or damage buffs, or even offer up one-time uses (per round). These things get really hard to track, especially when you start to pile up cards in play, as shown below. This level of memory is a major flaw in the design, which probably should have been accounted for in the components provided. Seeing this problem, we created custom components to track these things. In the photo, you will see the green tiles on the cards. This means that those cards’ one-time use powers have not been triggered. Once you use a power, you flip the token to the red side. Then, at the start of every round, you can reset all these trackers, assuming the card is still in play. This 100% streamlined this memory aspect of the game and allows us to focus on the fun parts of the game.

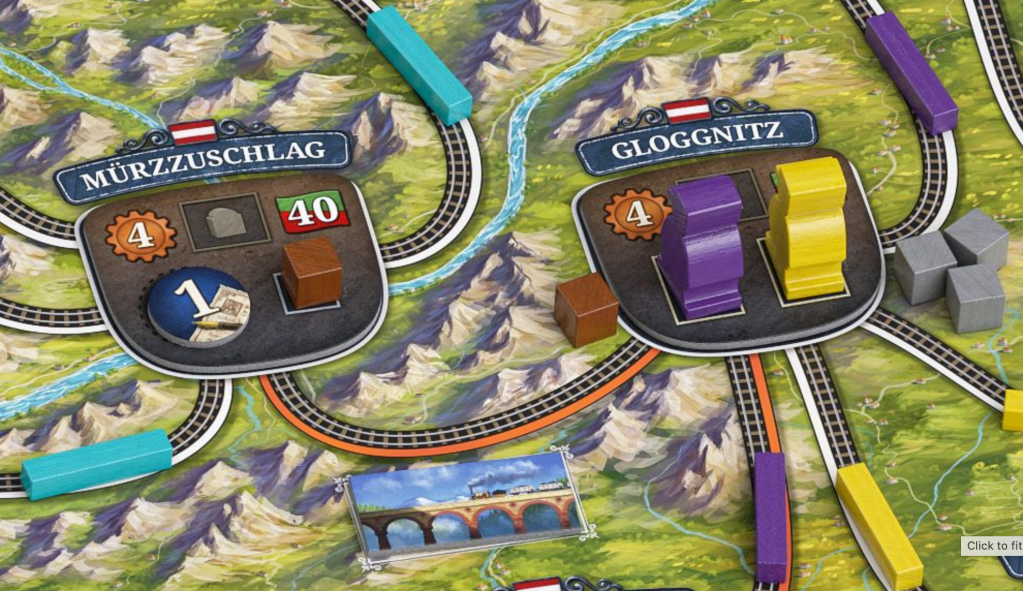

The game Imperial Steam has a few details that require memory of the rules and could have easily been fixed with a little bit of effort. Overall, the game does a good job of minimizing memory load, but there are a few cases that could be improved. For example, in the image below, we see 2 cities. If you’re the first player to connect these two locations, you collect the bridge token known as the Semmering token. This token doubles your endgame income and is a helpful little bonus. But players always forget and ask what it does. The game is, after all, rather complex and there is a lot to remember. They could have simply put the text on one side of the token to remind players, in context, what the token does. The game has a few minor details like this, which my local playgroup has added to the board to ease play.

How to handle memory

So what is the best approach to dealing with memory in our game designs? For me personally, I try to pay attention to the details players get wrong and the things they most frequently ask about or are confused by. Then I consider if the aspect in question is a feature or a flaw. Is the game supposed to use memory in that way? If not, then this is an indicator that my design is overloading their memory. From there, I look for a way to help them avoid the pitfall and smooth out gameplay.