As you analyze the top 100 games on Board Game Geek, a pattern emerges. Each of these games has very strong control over the mechanics. That is to say that most of these games have solid and clear core mechanics that simply do not require extensive exceptions or bolted-on mechanics to fix things.

Big game, tight mechanics

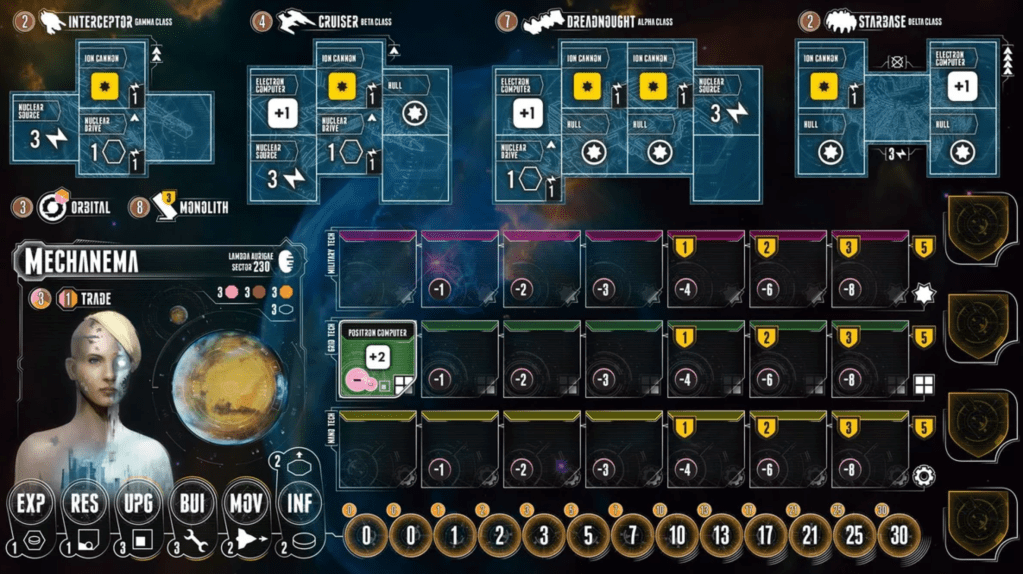

Despite its size and complexity, Eclipse: Second Dawn for the Galaxy only has 6 actions a player can take. These 6 actions never feel scripted. You will want to do more of everything than the system will allow you. This means that on most turns the choice of which action to take will be agonizing. Everything will have risks and benefits to what you do.

What I find interesting is that on the surface the 6 mechanics sound basic and not super interesting. But this is where the simplicity goes away. Each action, though it’s relatively simple in nature, presents an extremely wide range of executions. Take for example research. You will have a whole tray of things to pick from. So though this is a quick and simple concept, you have a huge sandbox to play in. And this is really where the game shines. Simple list to pick from, with extremely clear outcomes, and then a huge diversity of execution choices.

I don’t want to detail every mechanic in the game, but having just finished re-reading the rule book, I never felt that any mechanic was out of place. Everything in the game is born out of the 6 core actions. A few details on the player boards did stand out to me as worth mentioning.

Each faction you can choose from has some special atributes that make them unique. The factions are not radically different as in a game like Root. Instead they have just enough so that their special. As such the asymetry is super intentional and adds flavor or balances things out.

The second mechanic that I greatly appreciate is that when you add a tech tile to your board, it automatically creates a discount on your next tech tile in that row. This simple detail lets players add tech tiles in the order they choose. You can skip straight to an expensive one, or you can inch up to it so that you get it cheaper after buying several other techs. This detail means there isn’t a strict tech tree you have to follow. This keeps the evolution of your technology far simpler and allows the player more agency in the strategy they pursue. It’s such a simple little detail, but the impact on the gameplay and experience is just awesome.

There is only a single action you can do for free in Eclipse. It lets you activate your colony ships (which you start with) and move cubes from your tray to the board in regions you control. By doing so, you are boosting your income on the tracks those cubes come from. I suspect that perhaps this action was one you had to pay for at some point with an influence token (as you do for the other six actions). I am also guessing that this just felt too punishing and slow. Allowing this to happen more easily speeds the game up and gets you to the fun parts.

Little game tight mechanics

So how does the principle that each mechanic has a clear purpose work with a much smaller game? Scout is a great example of this. It is by far the simplest game in the current top 100 games on Board Game Geek. So what makes it so special? I would argue that the mechanics are super tight and focused. It is also super easy to teach/learn. And the game leaves the player a lot of agency and has plenty of room for players to level up their game play with stronger strategies. These all add up to a great game.

In Scout, when its your turn you can only do 1 of 2 things. You either play a new trick of cards that is stronger than the current one. Or, you steal one card from the current trick and add it to your hand. Finally, you can one time per round do both. That’s it. Nothing else is needed to make this game great. I am amazed how they made so little feel like a whole game.

Big game, sprawling mechanics

Finally, I want to look at a slightly less successful design. Granted, it’s still in the top 1,000 games on Board Game Geek. And it’s actually one of our favorite games. But looking at the very best games through the lens of a clear purpose for every single mechanic, I can’t help but wonder if this is where it slips a bit. The game I am talking about is Lords of Hellas. It’s a gorgeous game, with a great theme and very unique mechanics. Like I said, we greatly enjoy it. But mechanically, it does feel very different from a game like Eclipse. They are both huge in scale and involve a lot of rules. However, Lords of Hellas just isn’t nearly as simple or focused. Each section of the game has radically different rules.

In the game, there are 4 basic actions and 7 special actions. This is nearly twice as many as Eclipse. Each of these 11 actions requires a full explanation. Some of these actions, like “Hunt,” have whole sub rule sets to follow that are unique to that action. These actions and their mechanics are thematic, but somehow it feels more like a sprawling design. This is not to say that it’s a bad game at all. It’s just that it’s different, more complex, and the paths through it are less clear.

How to use this principle

So how do we put this to work in our own designs? If I reflect on my own game journey, it’s to recognize when a design requires too many special cases or too many “in this situation you have to do x.” When this starts to happen, it tells me the core of the game is not tight and clear. Regardless of the size of the game, it is possible to have that level of clarity. When I create something where you have but a few choices to pick from, and within each of those is a depth of choices to be made… then I know I am onto something. Perhaps this is my personal style of design, though. Regardless, I do feel like it’s an effective way to critique our own designs.

Some great questions to ask that might help you drive towards this goal:

- What mechanics are the least fun, and how can I get rid of them?

- How many choices do players have? And what can I do to reduce them?

- How much agency do players have in how actions are resoled? What can I do to increase this?

- Does each mechanic have a clear and obvious purpose as it relates to the theme and the experience I want to make?

- Are the core actions distinct and clear?

- Is the pace or speed of the game appropriate? What can I do to accelerate to the fun parts?

Sometimes it’s hard to do this with our own designs, though. But these are great pointers towards questions you can ask your playtesters.