A fundamental aspect of game design is that players can easily reach and see what they need. If it is too hard to reach or see the content, it will be very challenging to engage with it. This basic ability can have a very large impact on the player experience. Things that are too far out of reach may be ignored or forgotten. This could result in players missing key opportunities, or it might even lead to the game being played incorrectly. Considering whether players can see and reach needed elements is a topic that is drawn from the world of Human Factors.

What is Human Factors?

Human factors is the study of how people interact with products, systems, and environments. The goal is to improve safety, efficiency, and usability. Consider, for example, how people might interact with a ticket kiosk at an airport. Human factors would consider elements outside of the digital interface, such as the fact that users will be carrying lots of luggage, are likely to be in a loud environment, and might be distracted and stressed out. These human factors impact how effective the user will be at the kiosk. These extra considerations can be used when designing the interface and the physical kiosk. This same way of thinking maps perfectly to game design where players are interacting with physical components.

Bring the parts to the player

In the game Planet Unknown, players will be taking pentominoes from a central supply and adding them to their personal player board. The supply of tiles is stored in a round tray that rotates. This rotation serves two purposes. First, it limits which pieces you’re allowed to take. A player can only select from the pieces directly in front of them. Second, it ensures that the player has easy access. The limiting of your choices is a great mechanic in that it reduces the options the players have, thereby reducing analysis paralysis. But in terms of player experience, the way the game brings the parts to the players is just perfect. Finding harmony of elements like this can be challenging.

Another version of bringing the parts to the players can be found in the game Endeavor: Age of Sail. Each round, players will have the chance to acquire a new building to add to their individual player board. There can be up to 15 of these to choose from. All of these are stored in a nice tray that can be passed around. In this way, players will have the ability to see them up close and choose the one they want. I suspect this was originally done just as a nice way to store them, but it has the happy side effect of improving the player experience.

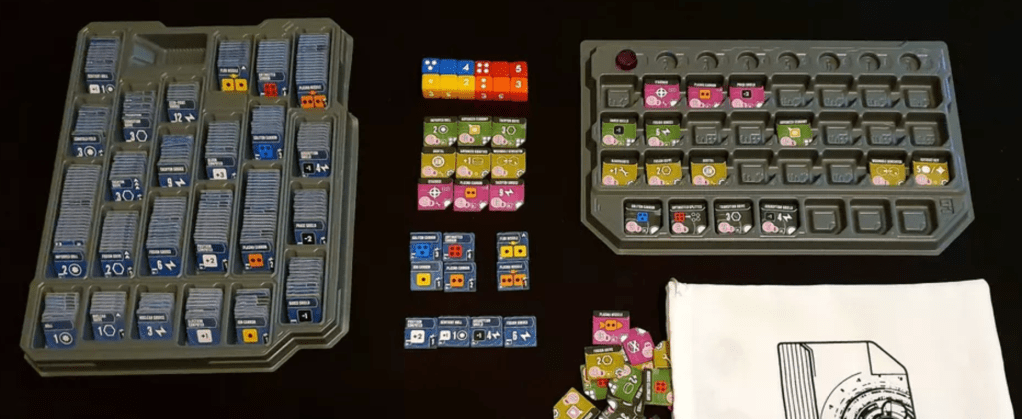

Another game with a similar mechanic is Eclipse: Second Dawn for the Galaxy. In this game, players have the chance to acquire tech tiles from a very wide variety. There can be 30 or more to choose from. In another action, players may add ship parts to their board. All of these interact, and you have to have the tech tile to get the ship part later. These two trays can easily be passed around so players can quickly identify what they can gain. The game would truly be a nightmare without these trays.

Consolidate when possible

Some games, due to their design, have parts that players simply have to be able to see on the board. And sometimes this will be a situation where a fair amount of content has to be consumed. This is a risky situation as it can result in a hard-to-play game. One game that has this problem, but overcomes it elegantly, is Cthulhu Death May Die. In this game, you select an elder god and an episode to combine. From this, you have four cards with custom actions, monster effects, and so on. These are all placed on the story board (the left board in the image below). In the latest version of the game, you can also add extra monsters to the episode. Those cards are added to the unknown monster board (right board in the image below). This is a lot to track. And to make things even more complicated, all of those cards have to be executed in a specific order. Fortunately, the game designers solved for this by not only providing these boards, but by also adding an order of operations to the unknown monster board. As a result, it’s just a matter of following the steps and doing what it says. It’s actually pretty easy. This is all great except when you have five players. There is simply no way everyone will have access to this information in a convenient way. What typically happens is that a single person becomes responsible for these boards. In this way, it is easy to see and access because that person should have it directly in front of them. And since the game is coop, this approach works really well. Typically, by the end of the game, everyone pretty much has it memorized what terrible things are going to happen to them.

A missed opportunity

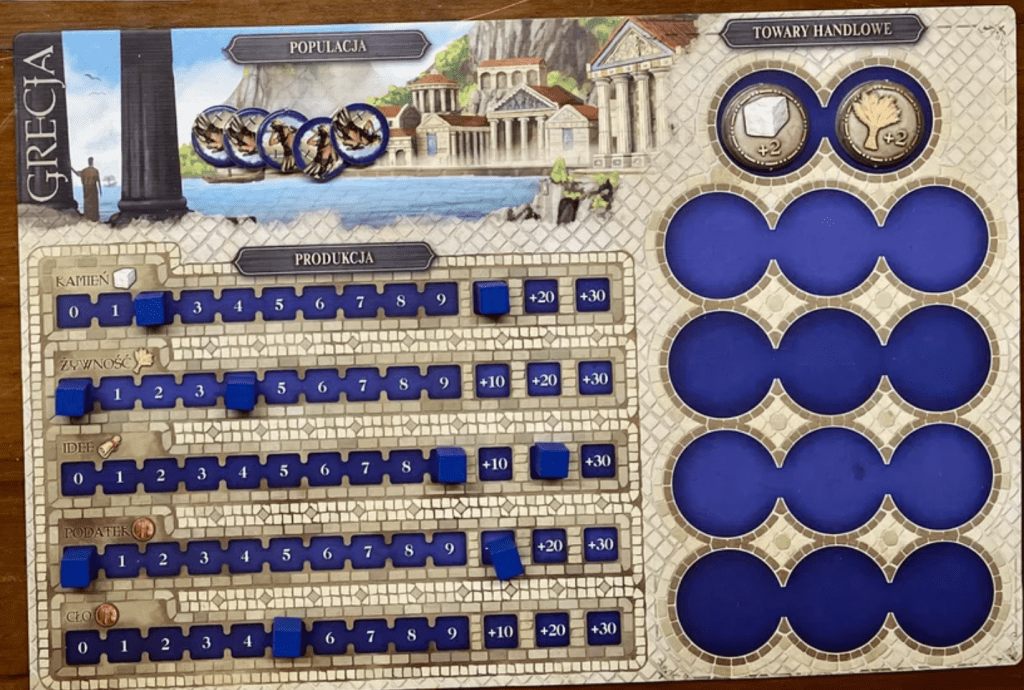

The game Mosaic: A Story of Civilization is a phenomenal game. One that my game group frequently brings out. The main thing players seem to get hung up on is the actions they can take and what the cost of those actions are. 100% of this information is on the board though. All of the cards in the image below are contained in the areas where actions may be taken. In each there is some smallish text that explains how that action works. So the information is there, its just kind of hard to read, gets covered by cards an it’s spread all over.

A simple fix to this would be to add this information to the player boards. There is plenty of room for it and it would eliminate this point of confusion.

Keep distant elements simple

Games often have a central play area and individual play areas for each player. One strategy is to keep the central area relatively simple and shift the most complex parts to the players board. In this way the most complex items are near to the player and will be easier to see and reach.

A good example of this is the game Clans of Caledonia. The central area of this game is super simple. There are no icons or other information. Its player pieces placed onto hexes. Each hex is a terrain type. And thats about as complex as it gets.

Another thing to consider with keeping the central area as the least complex is to have the central part be really big. The trend these days is for big overproduced games. In some cases, this naturally leads to a very easy-to-understand game state. In GKR: Heavy Hitters, the board is super simple and doesn’t have any tiny fiddle details. The fact that the parts are all gigantic is not only awesome looking, but helps players easily understand their status on the map. The 3D buildings make it even more clear what is happening.

Contrast this with War of the Ring. The board in this game has mountains that block movement; but they are super easy to overlook. The Free Peoples are all blue while the Shadow side is all red. But within those there are multiple factions, which is almost impossible to discern. So in GKR, you can instantly process what is happening, while in War of the Ring, you have to take it all in and try not to miss anything. Yes, there is more going on in War of the Ring, but these problems go away with a few very minor enhancements. We added 3D mountains and colored bases to all the figures, and now it has that same ability to be instantly understood.

Keeping the central area of the board easy to discern is important for enabling players to understand the game state. In playtesting, pay attention to where players seem to have the most confusion or questions. Then, consider how to make the information in that space easier to understand. You can prepare for this by simply considering if players can see or reach the needed elements. if not, your likely to be creating a poor player experience.

The last two games I want to compare in this are Century: Golem Edition and Century: Eastern Wonders. These two games are in a series of 3 that are meant to be combined or played individually. Given their close relationship, it’s interesting to compare aspects of these games. In the Golem Edition, the complexity is mostly in the players’ hands and the cards they have. In that sense the key information is easy to see and certainly easy to reach. In contrast, Eastern Wonders has all the icons on a central board. This information isn’t impossible to see or reach, but its definitely a tad harder since its farther away. These games are both fantastic, but it’s really interesting how the ease of gameplay is slightly different due to the location of the complexity.

The 6 zones of play

For additional reading on this, I encourage you to check out this blog post about the 6 zones of play or listen to it discussed on the Ludology podcast. It directly relates to the notion of ensuring players have easy access to see and reach the necessary elements.

Conclusion

As you playtest your game, pay attention to the physical space your game occupies. Can players see everything they need to? If it’s a central or shared element, you might need to make it bigger. Or is there any information you can move from the central area to the players’ personal space? Sometimes it’s easy to overlook this aspect of game design, but it’s definitely a factor in building a positive player experience.